Carry’s Rose; or, the Magic of Kindness. A Tale for the Young

Note, this story was written in the 19th century, in Victorian times. Stories in those days were often morally improving. You will also find that some ideas expressed in the story would be seen as totally unacceptable in the 21st century. The story has been printed just as it was written, apart from a couple of spelling errors and typos.

Or,

The Magic of Kindness.

A Tale for the Young.

by

MRS. GEORGE CUPPLES,

London:

T. Nelson and Sons, Paternoster Row.

Edinburgh; and New York.

1881.

CARRY’S ROSE.

Caroline Ashcroft stood by the trellised arbour on the lawn, along with

Daisy, her pet lamb, watching for the approach of the carriage which had

been sent to the railway-station to meet her papa and her only brother,

Herbert. This was the first time that Caroline had been separated from her

brother, who had been sent to school at a distance some months before

this; and as she had no sister or companion of her own age, she had felt

very lonely during his absence. In honour of his return nurse had dressed

Caroline in her new white muslin; and Daisy, after being carefully washed

till her soft fleece was as white as snow, had been decorated with a

beautiful wreath of flowers. She was so anxious to pull it off, that

Caroline was obliged to hold her head very firm, in case she should eat it

up before Herbert arrived.

“Now, Daisy,” said Caroline to the lamb, “just have a few minutes more

patience. I’m certain I hear the sound of wheels. There!” she cried,

clapping her hands, as the carriage turned in at the avenue gate. Daisy,

feeling herself at liberty, ran away across the lawn, tossing her head

and tearing the wreath to pieces; but Caroline was so eager to catch the

first glimpse of Herbert, who she felt sure would be looking out of the

window for her, that she did not notice how soon her morning’s labour had

been destroyed.

Caroline was a sweet-dispositioned child, affectionate and very

warm-hearted; at least nurse thought so, as she dressed her that morning,

and listened to her plans for Herbert’s amusement during his holidays. She

had banished from her mind all recollection of his wayward temper, and the

delight he always seemed to take in tormenting her and teasing her in

every way in his power, and only thought how nice it would be to have him

at home once more.

“Ah, Miss Caroline,” nurse had said, “I’m thinking you will be even more

pleased to see him set off for school again, unless he is much improved.”

“But Herbert is a big boy now, nurse,” Caroline had replied; “only think

what nice letters he writes from school, telling how he longs to be beside

us again, and always speaks so kindly of me. I know he will be good.”

Nurse made no further remark, except to say “she hoped it would turn out

so;” for she did not want to cast a shadow over Caroline’s happiness.

Certainly, when Herbert jumped out of the carriage, he seemed as glad to

see his sister as she was to see him; and though the wreath on Daisy’s

neck was gone, he admired the white fleece very much, and said that they

would go together some day to gather wild flowers to make another. Then he

had so many amusing stories to relate about his adventures at school, that

Caroline thought there could not be a better brother found anywhere. Her

mamma had often said that Herbert had a good heart if he would just

control his temper, and had often told Caroline to be very gentle with

him, for nothing but gentleness would soften him.

It was late in the afternoon when Herbert returned, so that bed-time

arrived long before the stories were exhausted; and the brother and sister

parted for the night with the understanding that they should set out early

after breakfast for a long walk, and to pay some visits to old friends and

neighbours. The next morning, when Caroline awoke, the first thing she did

was to jump out of bed and run to the window to see what sort of a day it

was; when, much to her vexation, she found the rain was descending in

torrents. She was far more sorry for Herbert’s disappointment than for her

own; for she remembered how he disliked a wet day, and how difficult it

always was for him to spend it comfortably. Still Herbert might not be so

foolish now, she thought, and she would try all she could to amuse him.

“Well, I must say this is too bad,” said Herbert, as he entered the

breakfast-room the next morning.

“What is too bad?” inquired his mamma, as she poured out the coffee.

“Why, the rain, to be sure, mamma,” replied Herbert. “Hasn’t it stopped

our plans for the day?”

“They were of such consequence, I suppose,” said Mrs. Ashcroft, laughing.

“Here have I been hearing from every quarter that rain is greatly needed

to help on the crops; and now when it has come, and all the farmers’

hearts will be filled with rejoicing, my boy is filled with dismay!”

“Oh, but, mamma, you must own it is very provoking to have a wet day the

very first one on my return,” said Herbert.

“Well, perhaps it is vexatious, when we think of you as an individual,

and banish from our minds the thousands it will benefit.”

“Now, you are laughing at me, mamma,” said Herbert sulkily.

“Nay, my son,” said Mrs. Ashcroft, “I am sorry for you. But let me see if

nothing can be done to make a wet day pleasant in-doors. I’m sure Carry

will do her best to help.”

“Might we make soap-bubbles, mamma?” said Caroline; “you said I might try

to do it some day with the pipe uncle gave me.”

“Well, I daresay you may, dear, if you put on an apron, and don’t wet

yourself.”

After breakfast Caroline was not long in getting the soap and water ready,

which she carried off to the school-room; and though Herbert at first

called it a babyish game, and stood apart by the window watching the rain,

he could not help joining his sister in the end.

“Oh, if you had only seen what lovely ones uncle made,” said Caroline,

“and how beautifully he tossed them up, making them float up to the very

roof without bursting sometimes!”

“That is not a very difficult process, I should say,” replied Herbert.

“Give me the pipe, and I will show you I can do it as well as uncle.”

Caroline at once gave up the pipe, and good-naturedly held the dish while

Herbert blew the soap-bubbles; and even he became fascinated with the

sport, and sat blowing away so long that lunch-hour arrived and poor

Caroline hadn’t had a chance to make another, though she wanted to do it

ever so much.

As the day advanced, and the novelty of being at home wore off, Herbert

began to return to his old habit of teasing his inoffensive sister. They

were sitting beside their mamma, who was sewing, while she listened with

as much delight almost as Caroline did to Herbert’s stories of his life at

school. Caroline was on the floor dressing her doll, while Herbert sat on

a low stool at his mother’s feet; but unable to behave himself longer, he

rolled over on to the floor, and, with his head in Caroline’s lap,

snatched the doll out of her hands.

“Oh, do give me my doll,” said Caroline, as gently as she could; “see, her

poor arm is broken, and the sawdust is coming out.”

“What a baby you are, Carry!” said Herbert, paying no attention to her

request. “No girl of your age plays with dolls nowadays. Stop; let me show

you how the jugglers do. They toss up a ball on their feet so,” and

Herbert flung the doll up in the air and caught it upon his feet, then

sent it spinning to the roof again, while he laughed at Caroline’s look of

distress.

Their mamma now interposed, and bade Herbert give the doll back at once,

telling him at the same time that he ought to be ashamed of himself for

tormenting his sister in such a way, and warned him that though it was his

holidays she would punish him most severely if he annoyed her again.

Herbert went off to his own room and got into bed, where he lay till

dinner-time. It was doubtful, however, whether he or Caroline really

suffered most.

“O mamma, it was my fault,” she said, while the tears stood in her eyes;

“I know Herbert was just in fun; I daresay he would not have done it any

harm if I had trusted it to him. He has often said it was the sight of my

frightened face that made him wish to go on; for it looks so funny to see

me so frightened, he says, about such a trifle.”

“That may be all very true, dear,” said her mamma, “but I do not like to

see Herbert giving way to such a disposition. It has grieved both papa and

me many a time to see our boy growing up with that constant wish to tease

and torment any helpless creature he meets, more especially his own

sister. We sent him to school to see if it would do him good; but I fear,

if it has checked him it has not cured him. I should like to see my boy

grow up manly and courageous; for it is only a cowardly disposition that

tries to tease a little girl or torment a dumb animal.”

Still Caroline could not help being sorry for Herbert, and when she saw

him looking, as she fancied, very dull during dinner, she slipped away

after him, thinking that he must be very unhappy, though all the time he

was just indulging himself in a fit of the sulks. At first he was

inclined to treat Caroline’s advances to friendship in a surly manner,

but a glance at her earnest, gentle eyes made him feel ashamed of himself;

and being at the same time tired of his solitude, he at length consented

to play a game at bagatelle. He even went so far as to say, “Well, after

all Carry, you are a good little thing; I do annoy you terribly, which is

not fair, because you are so forgiving. Well, to make up for it, I’ll be

very kind to you to-morrow.”

When Herbert came to bid his mamma good-night in her room, he had quite

forgotten that she had been angry with him during the day. He was very

much surprised, therefore, when, instead of kissing him, she pushed him

back from her knee, saying, “I fear I have no good-night kiss for you, my

boy, at present.”

“Why, mamma, what have I done?” said Herbert, the tears starting to his

eyes, for he knew that if his mamma refused to kiss him she must indeed be

angry.

“You surely have not forgotten how displeased I was with you this forenoon

for teasing your sister!” said Mrs. Ashcroft in a tone of severity.

“But, mamma, Carry has forgotten it now; and I told her I was sorry,” said

Herbert eagerly. “I’m sure all I did to her couldn’t hurt her so very

much.”

“Perhaps not, my son,” said Mrs. Ashcroft; “but you remember the reason

why we sent you away to school was to see if this bad habit of teasing

could be cured. If I had thought you were to begin the very first day you

were at home, I should have allowed you to stay at school during the

holidays also.”

“But there wasn’t one boy stayed behind at school this half,” said

Herbert; “you surely wouldn’t have left me all alone, mamma!”

“Indeed I would, Herbert,” replied his mamma firmly; “and what is more, if

you persevere in this bad habit, I shall speak to papa as to whether it

would not be advisable to send you back to school even yet.”

Herbert could not help seeing that his mamma really meant what she said,

and this threat frightened him so much that he wept bitterly. “Mamma,” he

said, “if you will only forgive me this once, I will try very hard not to

tease Carry all the time I am at home.”

“Well, my boy,” said Mrs. Ashcroft kindly, “we will give you one more

trial, and I hope you will not only try very hard, but ask God to help you

to be a good boy.”

Herbert, before he went to his own room, opened his sister’s door very

carefully to see if she were in bed. Carry did not hear him, she was so

intent looking out of the window at the rain. “I like to see the rain,”

she was saying to herself; “but I do hope it will pour itself out during

the night, for Herbert’s sake; it is very hard for him, poor fellow.”

Herbert pulled to the door very gently, and retired to his own room, with

the feeling stronger than ever that his sister was really “a good little

thing.”

The next morning was as bright as a morning could well be, with everything

out-of-doors looking fresh after the rain, so that when breakfast was

over, Herbert and Caroline, with the large dog Neptune, lost not a moment

in setting out for a long ramble into the country. At first Herbert seemed

to remember his words of the previous evening, and was very kind to

Caroline, helping her carefully over the stepping-stones at the river,

instead of frightening her as he used to do. Then he always held open the

gates of the different fields they passed through, shutting them after

her, instead of making her do it. He even stopped throwing stones at a

wounded bird in a field when he saw it distressed her, though he laughed

at her for being such a simpleton as to care for a half-dead bird. This

recalled to his mind a circumstance that had happened at school, when he

and some of his schoolfellows had gone for a walk into the country one

half-holiday; and he began to relate how they had caught a pigeon sitting

on its nest up a tree, and how, regardless of its fluttering and piteous

cries, they had carried it off, and its nest also. Then he told with much

laughter how they had unearthed a mole, and how they had tied it to a

stick and made it a target to fling stones at, till it had died by inches;

no doubt, as Caroline supposed, having suffered great torture. Losing all

command of herself, she cried out, “O Herbert, how could you, could you be

so cruel! It is quite true what mamma says, you are nothing but a coward,

to hunt a dumb creature, a poor blind animal, so.”

At these words Herbert flew into a passion, and told Caroline she might

find her way home the best way she could, for that he would not walk any

more with her; and away he ran, with Neptune at his heels. When he was a

few yards off, he turned and cried out, “I hope you won’t meet with Farmer

Brown’s bull, that’s all; and that you won’t find the stepping-stones

difficult, now that your coward isn’t there to help you.”

Caroline thought that he was only doing this to frighten her, and

expecting he would return in a short time, she sat down by the brink of

the river, wondering how boys could be so cruel to God’s creatures. Boys

were taught by their parents to be kind to animals, just as their sisters

were; yet, as they grew up, they forgot all about it,–at least, very many

of them did; and they seemed to try who would do the most cruel thing.

She sat trying to think of a plan to make her brother Herbert kind and

gentle; and again it came into her mind how by her own hastiness she had

made him angry just when he was doing everything to please her. “It was so

very dreadful of him to hurt the poor blind mole,” she said aloud; “I

could not help speaking out; only I need not have called him a coward. I

might have shown him how bad his conduct was in a gentler way; but, as

nurse and mamma say, I am always so hasty.”

Caroline having sat a long time, began to think that Herbert really did

not mean to come for her; and fearing her mamma would be alarmed if she

did not return with Herbert in time for dinner, she turned back along the

path they had come, walking as fast as she could. After passing through

two fields, and managing to open and shut the gates with some difficulty,

she was alarmed by hearing a loud roar, which she guessed must come from

Farmer Brown’s bull. She nearly fell down with terror, for the bull had a

very bad character for goring people, and had only the week before hurt a

little boy very seriously. Collecting all her courage, she crept round by

the side of the hedge. Fortunately the bull had his head turned in the

opposite direction, so that she managed to pass him and get out of the

field without being seen by him. At the stepping-stones she stopped,

afraid to venture over; but a man came up, who kindly offered to take her

across.

Going round by a field-path that led to her home past Farmer Brown’s farm,

she saw a little girl sitting under a tree, whom she at once guessed must

be little Martha, the farmer’s only child. She was gazing up at a flight

of pigeons that went fluttering over the houses before they lighted down

upon the roof of the barn. Caroline had often seen Martha at church, and

once or twice nurse had taken her to the farm, when she had gone to see

Mrs. Brown; so she stopped to ask the little girl what she was looking at

so earnestly.

“I’m looking at the pigeons, miss,” said little Martha, rising to drop a

courtesy to the young lady from the Hall.

“They seem to be all pure white,” said Caroline, sitting down on the roots

of the tree, and bidding Martha take her seat again. “They are very

pretty.”

“Yes, miss, they are pretty,” said Martha, looking with pride at her

favourites; “but they are not all white; there be two of them blue, and

I’m so sorry for it.”

“Why, what makes you sorry for the blue ones?” said Caroline, smiling.

“Don’t you like blue ones?”

“Oh yes, I like them very much,” said Martha, “but father doesn’t; and

he’s going to shoot them to-night.”

“Oh, how cruel of him,” said Caroline; “you must ask him not to do it,

Martha. They cannot help being blue, you know.”

Martha looked a little distressed at the idea of her kind father being

considered cruel by the young lady, but she didn’t know very well how to

answer her. “Father doesn’t mean to be cruel, miss,” said Martha; “but he

likes all the pigeons to be white; and if a blue one comes he shoots it. I

will ask father not to shoot them, and perhaps he won’t.”

“Oh yes, please do ask him,” replied Caroline; “and tell him if he only

could catch them, and send them down to me, I would give him my new

shilling papa gave me on my birth-day. Tell him to be sure and not to

shoot them.”

Martha went off at once to look for her father, but as he had gone away to

a distant part of the farm, Caroline had to be content to await his

return, and leaving the matter in Martha’s hands for the present,

proceeded on her way homewards.

When she arrived at home, she was very glad to find that her mamma had not

returned from town; so that, unless Caroline told her, she could not know

of Herbert’s bad behaviour; and Caroline was determined to keep it secret.

If Mrs. Ashcroft saw that the children were not such good friends as they

had been that morning, she took no notice of it, and during dinner spoke

more to their papa than to them. But towards the end she turned to

Caroline and said, “Who do you think is coming to pay you a visit of a few

days? Well, I shall tell you, as I see you cannot guess. Your two cousins,

Lizzie and Charles.”

Caroline was very much pleased to hear this, for she loved her cousins

very much; but her brother did not, for Charles was a well-behaved boy,

one or two years younger than Herbert, and would never join in any of his

tricks against the girls. When they arrived next morning, they went off at

once to see Caroline’s pet hen and chickens; and though Herbert went with

them, he stood aside with his hoop dangling on his arm, and with a look of

contempt on his face at his cousin Charlie’s delight at the sight of the

chickens. Living in a town as Charles and Lizzie did, everything belonging

to the country was new and delightful; and it was not till all the

poultry-sheds, and rabbit-hutches, and the very stables and cow-houses had

been visited, that Charles would consent to join Herbert in a game on the

lawn.

“I never saw any one like you, Charles,” said Herbert, with a sneer; “one

would think you never had seen a hen or a cow before. If you were at our

school they would call you ‘lady;’ for you clap your hands just as a girl

does over these things. I like horses and dogs, but who cares for a hen

and chicks?”

“Well, now,” said Charles, “can there be a prettier sight than a hen with

her chickens peeping out under her wings?”

Herbert made no reply, and the boys now set about having a game at

cricket, the girls good-naturedly agreeing to join in it, though they ran

some risk of being hurt; for Herbert often tried to strike the ball in

their direction, that he might enjoy the fun of seeing them run out of its

way lest it should hurt them. However, nothing of the kind happened; but

both Lizzie and Caroline were very glad when their brothers proposed to

put away the bat and wickets, and have a game at hide-and-seek down at the

great stack-yard. All that day and the next Herbert made himself very

agreeable, and a very happy time the four children had. On the third day

they paid a visit to old Mary Watkins, who lived in a little cottage on

the borders of Mr. Ashcroft’s property, and was a great favourite both

with the children and their parents. Old Mary had not been very well, and

Caroline and Lizzie were to take her some strong soup and some jelly, and

they were all to be allowed to stay and drink tea with her, if she was

able to have them. This was always considered a great treat, and no one

enjoyed it more than Herbert; for old Mary had such lots of stories to

tell, especially about her two sons, who were both sailors, but who had

not been heard of for some years. When they reached Mary’s cottage, they

found the old woman quite pleased to see them; and as she was not able to

set her best cups out on the tray with the large ship in full sail painted

on it, the girls were allowed to do it for her. The boys were very active

also in getting water from the spring to fill the kettle, which they

lifted up on to the large hook that hung so strangely down the chimney

over the fire.

Mrs. Ashcroft had taken care to send a good supply of provisions in

another basket, in case Mary should not be prepared for such a large

party; and they made a most hearty tea after their long walk. When the

cups had been washed and put away, and the tray admired once more before

it was placed up against the wall, there was still time to hear a good

many of Mary’s best stories before the hour fixed for their return home.

The next day the children were obliged to keep within doors, as it was

very wet; and, as usual, Herbert came in to breakfast looking as gloomy

as the weather, while his cousin Charles evidently intended to make the

best of matters, and was quite cheerful.

“Come, girls,” he cried, when they had gone up to the empty schoolroom,

“let us have a game at playing at school. Don’t you remember how we

enjoyed it last time?”

Herbert flung himself down on the floor in a pet at the idea of being

asked to play such a childish game; but though he tried hard to enjoy his

favourite book, and not to listen to their mirth, when Lizzie purposely

made such absurd mistakes, he was compelled at last to join in the

laughter, and then in the game itself. Afterwards they played a game at

bagatelle, but it took all their patience to stand Herbert’s whims and

tricks. He did not interfere with Lizzie, for she was on his side, but

when Caroline and Charles were going to play, he would stagger up against

them and cause them to play badly; or, if he saw that the ball was likely

to go into a large number, he would slyly lift up the board and make it

roll away.

“You said the other day that they would call me ‘lady’ at your school,”

said Charles, “but I know what they would call you at ours.”

“What’s that, pray?” replied Herbert, coming up close to his cousin with a

scowl on his face and his hand clenched behind his back.

Charles was not in the least afraid of Herbert’s threatening appearance,

but answered stoutly,–“They would call you ‘cheat;’ and of the two names

I’d prefer ‘lady.'”

Herbert was neither restrained by the fact that his cousin was a guest in

the house nor by the difference in their age, a double reason for treating

him with forbearance.

Before Caroline had time to prevent him, Herbert had struck Charles a

severe blow on the head, which knocked him down; and as he lay for some

minutes almost senseless, the girls thought he was going to die, and

screamed out for help.

Fortunately, nurse was passing the schoolroom door at the time, and

hearing the noise, came in. Charles’s face and head having been bathed, he

soon recovered; and as Herbert seemed to have got a terrible fright, and

to be truly sorry for his conduct, Charles was quite willing to forgive

him, and to shake hands in token of friendship. During the remainder of

their visit Herbert was very attentive to his cousins; and if any game was

proposed by them, whether he thought it babyish or not, he never raised

the least objection, but joined quite heartily in it.

Yet he had not given up his bad habits altogether; for he still went on

with his teasing ways to his sister Caroline, both before his cousins’

face and behind their back, till she began to think that, after all, as

nurse had said, she would be glad when his holidays came to an end.

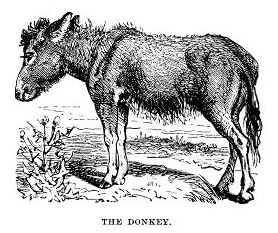

A few mornings after this, the children set out to fish in the river, and

while walking round by the common they came upon a donkey standing all

alone, without a bridle or even a rope on it. It was close to a large

juicy thistle, but it did not seem to be eating it, and every minute or

two it shook and trembled.

Lizzie was the first to notice it, and going closer, exclaimed, “I am

afraid the poor beast must be ill.”

“Tuts, what nonsense!” said Herbert; “donkeys are never ill. Don’t you

know they live for ever, Cousin Lizzie?”

“Well, I don’t know about that,” said Charles, going close up to the

donkey and looking into its face; “all I can say is, if this poor beast

isn’t ill it looks very like it.”

“It’s nothing but a stubborn fit,” said Herbert; and before any one could

stop him he gave the donkey a lash with a switch he held in his hand,

calling out at the same time, “Gee up, Teddy! come, get out of your sulks,

sir!”

The donkey’s flesh seemed to shiver, and he breathed harder, but his heavy

eye never brightened.

“I tell you what it is, Herbert, I’ll not see that poor animal ill-used in

that manner,” said Charles; “he’s not sulky, he’s ill!”

Herbert felt inclined to quarrel with Charles for his reproof, but Charles

had spied a little boy sitting on a gate herding a cow, and he ran over to

him to make inquiries who the donkey belonged to.

“Well, sir, the poor beast belongs to some travelling gypsies who are

living t’other side of the common, and they left it here this morning

because it couldn’t go no further, and there it has stood before that ‘ere

thistle ever since.”

Caroline now came up, and hearing that the donkey was ill beyond a doubt,

she proposed they should go home and ask their mamma to send the stable

lad with a hot drink to the poor animal. “I know when our pony was ill one

day he got a hot drink and some medicine, and he very soon was all right

again.”

“I’m not going back, for one,” said Herbert; “the idea of making such a

fuss about a donkey; it’s quite ridiculous!”

“Nobody is forcing you, my dear cousin,” replied Charles cheerily; “you

may go on to the river by yourself; but I for one couldn’t enjoy myself,

unless I had done something to help this poor animal in its distress.”

“Well, I don’t see why we all should stay because you choose to doctor an

old donkey,” said Herbert peevishly. “Come along, Lizzie and Carry; if you

don’t come at once we’ll lose the best part of the day, and get no fish.”

The girls, however, were quite as anxious about the welfare of the poor

donkey, and declared their intention to stay with Charlie. They even did

more, for they volunteered to go back to the house to get what was

necessary for the animal, while Charlie and the herd-boy watched by him,

ready to render any assistance if he should turn worse.

Caroline was fortunate in finding Stephens the gardener, who was

considered very skilful in doctoring sick animals; at any rate, he had set

the leg of one of her chickens when it was broken, and managed to bring

Neptune through a severe illness, therefore it was to be supposed he could

cure the donkey also.

“Well, miss, I’ll come and see him,” said Stephens; “but if he is as bad

as you say, I fear it’s little I can do.” To their great delight, however,

when Stephens had examined him, he gave it as his decided opinion that the

animal was suffering from a severe cold and over-work. “If we had him put

into a warm house for a night, and gave him something warm to eat, I think

he would soon be all right,” said Stephens. “I might manage to make him up

a bed in the root-house, if your mamma would have no objections.”

Caroline and Lizzie ran back to the house again, and after telling the

story, Mrs. Ashcroft gave permission that all attention should be paid to

the sick animal; and while Charles and the herd-boy went over to the gypsy

encampment to tell where their donkey had disappeared to, Caroline and

Lizzie helped Stephens to make the donkey comfortable. Even in the short

time they were beside him the poor animal seemed to be much relieved; and

though at first he could scarcely open his mouth to eat the warm, soft

mash Stephens had prepared for him, before they left he was beginning to

nibble at a tuft of hay that had been placed for his use.

“Oh, I do wish Herbert had stayed to help us,” said Caroline; “I really

cannot understand why he doesn’t take an interest in dumb animals. I

wonder why he is so different from Charles. Your brother is seldom cross

with you, not even when you are cross with him.”

“No,” said Lizzie; “he is really a good kind boy; but I know somebody, not

very far off, who is just as good and gentle as my brother Charles,–and

that is yourself, you patient little puss.”

“Oh, don’t say that, Lizzie dear,” said Caroline, with flushed cheeks.

“I’m often hasty and ill-tempered, and make Herbert worse than he might be

if I left him alone.”

“Well,” replied Lizzie, “all I can say is, if Herbert were my brother, I

should be twice as hasty and five times as ill-tempered, for he is about

the most provoking boy I know.”

Charles returned in due time from the gypsy encampment, quite delighted

with all he had seen of the people, and reported they had given up their

donkey for lost; and, of course, they had been much gratified to hear it

was likely to be restored to health and strength.

“I made them promise to leave the poor animal with us for a week,” said

Charlie; “and they say that they are quite willing, and mean to go on to

the market-town, and return again for him.”

“Oh, I was hoping they would remain in the wood for some time,” said

Lizzie. “I should like to see a gypsy encampment so much.”

“And so should I,” said Carry. “Nurse is always so frightened for the

gypsies, she won’t allow us ever to go near them. But, perhaps, when we

take the donkey back they will be civil, and not steal our clothes from

us.”

“Does nurse say they will do that?” said Charlie. “Oh, what a shame! I

wouldn’t believe it. They were so polite to me; and one old woman insisted

upon telling me my fortune, and when I offered her a sixpence she wouldn’t

have it.”

“And I suppose she told you some rubbish,” said Herbert; “sent you riding

off in a coach-and-four with your pockets full of money and your barrels

full of beer?”

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said Charlie, “she wasn’t half so kind. She said

I would grow up to be more than six feet high; that I would be a soldier

or a sailor, which I don’t intend to be; and that, after a great many

difficulties, I would succeed in the world, and mumbled something about a

clear opening and a straight uprising.”

“That’s because you didn’t give her any money,” said Herbert, laughing.

“Well, when they come back we’ll have her to tell us ours,” said Lizzie,

“and see if the coach-and-four is to fall to our lot.”

“But I don’t think mamma would like us to have our fortunes told. I know

she was very much displeased with one of the servants allowing the gypsy

woman to tell her hers. If we want to see the encampment, we had better

not have anything to do with the fortune-teller. Mamma says it is not only

silly but wicked to inquire into futurity.”

In about a week the gypsies returned; and the donkey being much better, he

was taken over and restored to his rightful owners. He was so much

improved with his rest and good treatment that they hardly knew him, and

the whole of the gypsy children belonging to the encampment gathered round

to see their old friend and companion. When the children from the Hall

left, after inspecting the queer tents and everything else, they turned

to look once more at the donkey and wave a good-bye to the gypsy man; and,

as Carry said, poor Punch–that was the name of the donkey–was looking

wistfully after them, and if the man hadn’t held him firm, he seemed

almost inclined to run after them. “Poor beast,” as Charlie said, “after

all his hard years of labour it was no wonder if he wanted a rest now.”

The morning after Lizzie and Charles left, Caroline was unable to get out

of bed with a sick headache, but was able to be down to dinner, where she

found Herbert with rather a grave face, which did not escape the notice

of his mamma; but as he always said, in answer to her question, there was

nothing the matter, she thought he was only in one of his bad humours. She

then told Caroline that she had seen little blind Susan, who was asking

when she was to get another flower.

“I was just waiting for my china-rose to come out,” said Caroline; “there

is one bud on it, and you know I said Susan was to have the first rose,

mamma.”

If Caroline had looked at Herbert she would have been surprised to see his

face become suddenly red; for the truth was, the rose-bud that Caroline

had watched so carefully was hanging from the stem broken; and more than

that, a great many flowers in her garden had been destroyed. It had

happened in this way. Finding that his mamma had gone out, Herbert went

into the garden with Neptune following closely at his heels. He had been

forbidden to take the dog into the garden, but, trusting to Neptune’s

obedient disposition, he thought he could keep him on the walks. He did

not expect to find a cat lying asleep under one of the garden-seats, else

he would have acted differently; for Neptune had a terrible hatred to

cats, and nothing could cure him of it. Therefore, when his eye fell upon

the cat, he bounded off after it, and, regardless of the flowers, chased

it right through Caroline’s little border.

Herbert was very sorry, more so when he remembered how his sister had not

told of his bad treatment during their walk by the river; but he was so

afraid of his papa’s displeasure, when it became known that he had taken

the dog into the garden, that he made up his mind he would deny all

knowledge of it. He was startled to hear his mamma telling Caroline it

would be better to pull the rosebud now, as it would come out just as well

in water, and last longer than if it were full-blown; so that if she liked

to get it now, she might go with nurse, who was going to take some

medicine to Susan’s sick mother.

Caroline, who was always glad to pay a visit to blind Susan, went away at

once into the garden, where she found Stephens the gardener leaning on his

spade and rake, and gazing down in dismay at the broken and crushed

flowers.

“O Stephens, who has done this?” said Caroline, almost ready to cry. “My

beautiful rosebud broken, my poor flowers destroyed!”

Then Stephens told how he had seen Master Herbert walking about the garden

with Neptune, and that, as he was at a distance, the flowers had been

destroyed before he got up to the place. “But Master Herbert shall suffer

for this,” said Stephens; “I mean to tell his papa about it this very

night.”

Caroline knew well how severely Herbert would be punished, and her heart

softened towards her brother. “Has Neptune done any harm to the other

flowers?” she asked Stephens.

“No, miss,” said Stephens; “for, do you see, the cat ran up that tree

there, and got over the wall, and the dog kept dancing about among the

flowers, trying to get his heavy body up after it.”

“Well, Stephens,” said Caroline, “since only my flowers have suffered,

will you please not tell papa this time? I can get up early in the morning

and tie them up a little, if you could help to rake it smooth for me.”

“That is very kind of you, miss,” replied Stephens, admiringly; “but what

about the rose you have been watching so carefully all this week?”

“Isn’t it strange?” said Caroline; “I came to pull it at mamma’s request,

and see, it is only broken with quite a long stem to it.”

To Herbert’s great surprise, Caroline returned with a bright smiling face,

and said nothing about the state she had found her garden in.

The next morning Caroline got up much earlier than her usual time for

rising, but not so early as she intended, for there was a good deal of

hard work before her garden could be made neat again. Dressing herself

quickly, she ran out, not even taking time to put on her bonnet, so eager

was she to begin; when to her surprise, there was Herbert busy at work

with a trowel smoothing the ground and propping up the earth round the

crushed flowers. She stood for some time scarcely believing it possible,

half thinking she must be dreaming; for Herbert was so fond of his bed,

once he was in it, that it was always a very difficult matter to get him

out of it. Now here he was, at six o’clock in the morning, hard at work,

as if his very life depended upon it. She ventured at last to step close

up to him, and tapped him on the shoulder, not very sure whether he would

feel angry or pleased to be caught at his novel employment. She did not

notice that her mamma was standing by the garden gate; for Mrs. Ashcroft,

having a bad headache, had got up early also, and had come out, in the

hope that the morning air would take it away.

“It is very good of you, dear Herbert,” said Caroline, while their mamma

paused to look at her children. “I was just coming to arrange them, when I

find you, like that kind fairy-man in my new book, setting everything in

order.”

The idea passed through Herbert’s mind for a moment that perhaps Caroline

did not know how her flowers had been broken, and so he need not tell her

he had had anything to do with it. He had felt very miserable ever since

it happened, thinking that his papa would be certain to find it out and

punish him, and at the same time he was ashamed when he thought of his

unkind treatment of his sister. It was only for a moment he hesitated,

however; then turning frankly round, he said, “I am very sorry, Carry,

your garden has been destroyed. It was all my fault, but I did not mean

it. I took–”

“Yes, I know,” said Caroline, interrupting him; “but don’t say any more

about it, we can easily get it put right again; indeed, you have done a

great deal already. How early you must have been up!”

“Yes,” said Herbert, with a smile; “I was down here when the clock struck

four. I was up even before the sun. But I must say, Carry, it is good of

you to pass it over. I won’t forget it in a hurry, I can tell you.”

Caroline asked him not to say another word about it, and, as she turned to

go to the tool-house, she saw her mamma looking at them very seriously.

Herbert, with downcast face, was compelled to tell how disobedient he had

been in breaking through his papa’s express order not to take Neptune into

the garden. His mamma was very angry with him, but after giving him a

severe scolding, she said she would not punish him this time, as he had

tried to repair the damage done by getting up so early, and also because

Carry had made the request after being the chief sufferer.

As it was still early, their mamma bade them run for their hats, and she

would take them a walk till breakfast was ready. Before they set out, she

gave each of them a drink of milk and some biscuits, as they were not

accustomed to be out so early. It was a lovely morning, and the children

enjoyed the walk very much. As they were returning home, they passed by a

part of the park where their papa allowed a number of sheep to graze; and

as they were looking over the paling, one of the sheep came close up to

them and began to bleat.

“I am sure, mamma,” cried Caroline, “that must be my pet lamb’s mother;

can she be wanting me to bring Daisy back again to her, do you think?”

“Well, I scarcely think it is likely, dear,” replied her mamma; “but how

do you know it is Daisy’s mother?”

“Because she has a queer sort of tuft of wool on her forehead,” said

Caroline, while both her mamma and Herbert laughed at her for supposing

that no other sheep but Daisy’s mother had a tuft. “It really is,” she

said decidedly, though joining in the laugh. “Oh,” she continued, “what a

pity a pet lamb grows up into a sheep. Only think of my poor Daisy’s white

face getting dirty and torn like that great stupid-looking sheep over

there!”

“Yes, I used to think so too,” said her mamma, “when I had a pet lamb.”

As they came round by the wood on their way home, Caroline said she would

like so much to get some of the beautiful wild-flowers for her garden.

Herbert did not say anything at the time, but he determined to get up

early the next morning also, and give her a pleasant surprise by getting a

basketful for her. One might have expected that before the next morning

came he would have quite forgotten all about it; but no; when the servant

called him at six o’clock, as he had requested her to do the night before,

he jumped out of bed at once. He knew of a deep dingle at some distance

from the house, where many kinds of wild-flowers were to be found; so he

made up his mind to go there instead of to the wood. The dingle was down

in a woody hollow, such as the “Babes in the Wood” might have been lost

in; and there were so many plants and ferns, that Herbert was often at a

loss what to choose. However, his basket was full at last, and he hurried

home, hoping to have them all planted before Caroline came down-stairs.

When he was planting them it came into his mind how much improved

Caroline’s garden would be if there were a small arbour at the side of it;

and he determined to ask his mamma’s permission to get the wood, and make

it during his holidays. When he went into the dining-room, after carefully

washing his face and hands and changing his muddy boots, he found his

mamma standing with an open letter in her hand, reading it aloud to his

papa.

It was from his grandmamma, who lived some miles from them, and who had

written to ask if Caroline might be allowed to spend a few days with her,

to help to entertain their two cousins, Harry and Maud, who had just

arrived from Australia. Herbert had got into disgrace during the last

visit he paid his grandmamma; but still he felt vexed at being left out of

the invitation, as he was curious to see these new cousins. His regret

was softened, however, when he thought there would now be a good

opportunity for making the arbour, so as to repay Carry for the injury

done to her garden. This thought made him very glad. It was decided that

Caroline should go that same day, and as she had a great deal to do in

helping nurse to pack her little trunk, and give directions about her

numerous pets, she did not once go near her garden.

Herbert could not help saying before she left, “I am so sorry I am not a

kinder brother to you, Carry; I do mean, however, to be better to you in

the future.”

“Oh, don’t say that, Herbert,” replied Carry; “I know it’s just in fun,

and I am so stupid to look vexed. I love you dearly, for you are my own

kind good brother,” and she clasped her arms round him in a fond embrace.

“That’s all very well,” said Herbert, returning the affectionate pressure;

“but I am sure I am not like Cousin Charlie. He is a kind brother really,

and always seems to be able to do and say the right thing at the proper

time; and as for being cross with Lizzie, he would sooner think of

flying.”

“Well, we shall say nothing more about it, dear,” said Caroline kindly.

“All I have to say is, I’d rather have you for my brother, though Charlie

is as good a boy as ever lived, I do think. Let us forget everything

disagreeable to-day, as I am to leave home so soon. Oh dear! I was

forgetting; I promised Daisy, my lamb, I would have a romp with her before

dinner, and the bell will ring very soon!”

They at once ran off, and getting the lamb from its snug house, proceeded

to the wood, their favourite resort.

“I wonder whether she will know you when you return,” said Herbert, as he

stood watching his sister tying a bright piece of ribbon round her lamb’s

neck.

“O Herbert, please don’t say that!–what a dreadful idea!” replied

Caroline. “I really don’t think she will ever be so ungrateful!–indeed, I

am sure she will know me if I stayed away ever so long. Now, Daisy, am I

not right?” she continued, kneeling down before her pet; “you will love me

always, even after you are a great fat sheep, and I have grown up into

quite a big girl.”

Daisy seemed to be quite impressed with the solemnity of the occasion,

and put out her black tongue to lick her mistress’s hand, as much as to

say, I will never forget you–never.

“Now, Herbert, you see I have tied the little bell round her neck, and if

Miss Daisy goes where she ought not to go, you will hear her and can put

her out; but I hope she will be a very good lamb, and trouble nobody.”

“I’ll look after her, never you fear,” said Herbert cheerily; and hearing

the dinner-bell, they returned to the house.

When she was safely off, Herbert told his mamma of the plan he had in his

mind; and as she was very much pleased to see that her boy was trying to

“turn over a new leaf,” she gave her consent at once, and said that

Stephens might take the pony-cart and help him to get the poles and wood

he required from the saw-mill. Early and late Herbert was at work, and so

diligent was he that his mamma had often to stop him, in case he should

hurt himself.

“I am afraid,” he would say, “Carry will be home before it is done. I do

so wish to surprise her. I can’t help thinking, as I work here by myself,

mamma, what a kind-hearted, good little thing Carry is; and I hate myself

when I think how I have vexed and teased her all her life.”

His mamma spoke very seriously to him, pointing out how much happier he

must feel by trying to please his sister than by vexing her; and saying

that poor Carry’s sweet, gentle disposition might have been spoiled

altogether, if he had not been sent away from her to school. “Ah,” said

Mrs. Ashcroft, “you ought to have seen how she missed you, and how she

wandered about for days after you left, with such an unhappy little face!

You ought indeed to love her, Herbert, and be proud to do her a service,

because she is a good sister to you.”

Herbert manfully said he meant to be a good brother for the future, and

never to tease her any more, for he saw he had been nothing but a coward

all along.

The day before Caroline returned, the arbour was quite finished–a perfect

model of its kind. There was a walk up to it, and a little flight of

steps; and Stephens had transplanted a beautiful clematis, and, as the

weather was very favourable, it had grown quite large, and gave Herbert a

great deal of work training it. There was a seat inside all round, and a

little table in the centre for Caroline to put her work-basket on; and on

the table was painted, in bright red letters, “A token of love to my

gentle sister.”

And now it was Herbert’s turn to watch for the arrival of the carriage;

and when it drew up at the front steps, he found not only Carry’s face

looking out for him, but there were his new cousins, Maud and Harry also;

and, though he could not see him, he heard the well-known voice of his

cousin Charles, and the merry laughter of Lizzie also. There never was a

happier meeting of girls and boys, and while Charles as usual ran off to

pay a visit to the various animals, taking Harry with him, Herbert

carried the three girls away to see the new arbour. Though Herbert had not

done it for praise, he got plenty of it, for every one pronounced it a

perfect beauty; and Maud, who did not of course know Herbert, said he must

be the kindest of brothers, to take so much trouble; and though Lizzie

might have told her it was quite a new thing for Herbert to be kind, she

kept her knowledge to herself, only saying it was a perfect beauty.

Stephens, of course, was praised for his share in the labour; and the two

boys were as delighted with it as the girls were, and only wished they

could make one also when they went home.

When Caroline got Herbert by himself for a few minutes she thanked him

very much for his gift, for she alone knew what had prompted him to make

it; and ever after the warm affection Herbert showed for his sister was

remarked upon by all who knew them.

While Caroline had been staying with her grandmamma, the gardener had

caught a young starling, which he had tamed, and seeing that the young

lady was very fond of birds and beasts, he asked her if she would accept

of the starling to take home with her. Caroline, as may be supposed, was

delighted with the offer, and thanking the gardener for his kindness, ran

off to ask her grandmamma if she might be allowed to take it. Of course it

was a mere form, for she might have known her kind grandmamma would never

say No to any request of the kind. Only Caroline was a polite little girl,

and always asked her parents’ permission first. She did not, when they

considered it necessary to refuse any request she made, keep saying, “Ah!

you might, mamma,” or, “But why, papa?” as I have heard many children do.

No; she was certain the refusal came for some wise object, and she tried

to bear the disappointment bravely.

“Oh, certainly, dear,” said her grandmamma on this occasion; “you may

have the bird, if you can manage to find time to take care of it; but I

think you have too many pets already.”

“What a funny idea, grandma,” said Caroline. “I couldn’t have too many

pets. But I will tell you what I mean to do with it. I am going to take

great care of it till Herbert’s birth-day, and then I am going to give it

to him.”

“But you will have to look after it all the same,” said her grandmamma,

laughing; “for Herbert will go to school immediately after his birth-day.”

“I shall like to do it, though, very much, grandma. I take care of his

rabbits, and Neptune, you know,” said Caroline; “and he said I had managed

them beautifully.”

Carry got the bird, it was taken home, and every day she hung the cage out

of her bed-room window, and gave him a bit of nice sugar, and the starling

became very tame. At night it was always taken into the housekeeper’s

room, and hung upon the wall there; and the good Mrs. Trigg was very kind

to it, though a starling was by no means the cleanest bird that one could

have. “You don’t think Tom will touch it?” said Caroline, the first night

the bird was there. Tom was Mrs. Trigg’s favourite tabby cat; and really,

to look at him lying on the rug, winking and blinking before the fire,

paying more attention to the kettle hissing and boiling away than to any

bird, Caroline could not help feeling a little ashamed of the question.

“Oh, Tom has got over all that kind of wild pranks, Miss Carry,” said Mrs.

Trigg. “He is wondering why I am delaying to infuse my tea, for Tom likes

his drop tea as well as his mistress.”

“Then I must not detain you longer,” said Caroline, knowing that Mrs.

Trigg did not like to be put past her tea-hour. “Mamma says that, if

convenient, we are to drink tea with you some night soon, and my cousins

are quite anxious to be invited also.”

“I would be a little nervous, miss, at entertaining such a large party,”

said Mrs. Trigg, but looking quite pleased nevertheless.

“Oh, you must ask us all,” said Caroline, laughing; “when shall I come to

write the invitations for you? To-morrow night?”

“Well, miss, if you think you could be happy in my room, we will say

to-morrow night.”

The invitations were duly sent out, Mrs. Trigg requesting the pleasure of

their company on the next week; and each of the children received a

separate note of invitation–and each, of course, had to reply, accepting

the invitation, in the same manner. But on the very morning of the

tea-party, when Caroline rose from her bed a little earlier than usual–as

she had promised to help Mrs. Trigg to prepare for the great event–and

when she had dressed and gone down to the housekeeper’s room, what was her

horror to see Tom, the tabby cat, on the top of the table, ready to spring

upon the cage where the unfortunate bird was. She gave a terrible scream,

which had the effect of scaring away the wicked cat; but the poor bird had

evidently been so frightened at the glaring green eyes that tried to

fascinate it and lure it to its ruin as a serpent does its prey, that it

fell down to the bottom of its cage in a fit.

“Oh, my poor bird,” cried Caroline; “it’s dead. Oh, do come quick and help

me.”

Mrs. Trigg was not far distant, and hearing the cries of distress,

hastened to her room, crying, “What’s the matter, Miss Carry? Oh, have you

hurt yourself?”

“No, no,” said Caroline; “it’s my bird. Tom has killed the poor thing. Oh,

what am I to do?”

The bird fluttered at this moment, and Mrs. Trigg took it out of the cage,

and holding it before the fire, declared it was still alive, and might

recover. Everything was done for it that could be thought of to restore

the poor bird, but all to no effect, for during luncheon it died. Caroline

was terribly grieved, and declared that the tea-party must be put off, for

it was impossible she could join in any game after such a sad event. But

then, when Mrs. Trigg mentioned that she had made a great many cakes, and

that they would be quite spoiled even if allowed to stay till the next

night, and also that she was going to be very busy preserving her fruit

for the winter, Caroline thought she must try to go to the party. “I

needn’t play, you know, Mrs. Trigg,” she had said. “I can just sit and

look on; for, of course, the others didn’t know what a dear good bird my

starling was.”

After tea, Caroline curled herself up into Mrs. Trigg’s chair, and sat

watching the others while they played. Pincher, Maud’s dog, who had come

with them, was very troublesome, and would hunt after the slipper as

eagerly as the boys did, poking his nose into their faces, and sometimes

even licking their ears with his tongue; and as they had their hands

tucked under them, they could not stop him. Then, when Herbert flung the

slipper over to the other side, and Harry made a grasp at it to get it out

of sight before Charlie could get round, Pincher made a rush after it too,

barking and yelping in his determination to catch this extraordinary rat

or rabbit.

“I tell you what it is,” said Herbert, “we must have Pincher put out of

the room.”

“Oh, don’t put him out,” pleaded Maud; “let us tie him up with his

ribbons. Perhaps, Carry dear, you wouldn’t mind holding him?”

Caroline was very happy to be of use, and held Pincher very securely. The

poor dog often looked up in her face as if to say, Are you being punished

too? and then, while still looking at her, made little springs and barked,

as if to encourage her to rise in rebellion and escape from her

persecutors. He was really so droll that Caroline could not help laughing

very heartily at him, and Herbert and her cousins were so glad when they

heard it, that they left off their game at once, and came over beside

her.

“I say, Carry, do come and play,” said Charlie; “we can’t feel happy

without you.”

“It is very sad about the bird,” said Harry. “I know when my green

parrakeets died on the voyage home from Australia, I was so sorry that I

actually went to bed. But I’ll tell you what we shall do: Herbert and

Charlie and I will catch another starling, and then you can tame him, and

keep him out of Tom’s reach for the future. Mrs. Trigg says there are lots

to be had in the steeple of the old church.”

It was not till next morning that Harry discovered why Caroline wanted to

have the starling; and no sooner did he understand that she wanted it for

a present for her brother, than he said in his prompt way, “Will nothing

else do? I tell you what, I saw a splendid thing that I am sure he will

like quite as well. If aunt would only let us go to the town we could get

it without him knowing.”

Caroline gladly promised to ask her mamma’s consent, but when she inquired

what this wonderful thing was, Harry only laughed and said, “No; I’ll keep

it secret till to-morrow. It is enough to ask a girl to keep one thing

secret at a time. Remember, if aunt consents, we must set out to-morrow

before anybody is up.”

Mrs. Ashcroft having given her consent, Harry and Caroline set out the

next morning, followed by Neptune, who insisted upon accompanying them.

“You had better take my arm, Caroline,” said Harry; “and let me carry your

basket, too. We have rather a long walk.”

At the town, Harry went straight to a shop where they sold all sorts of

animals both alive and stuffed, and when they had gone inside, Harry

pointed to a beautiful stuffed squirrel, and said, “That’s the thing that

will please Herbert.”

Though the squirrel was only stuffed, it looked so like a real live one,

that Caroline too was quite delighted with it, and said she would be so

glad to have it, only she hadn’t so much money of her own. “Oh, never mind

about money,” said Harry, “To tell you the truth, I meant to have bought

it for you the other day when I was here with Charlie. Now, if you like

to give it to Herbert on his birth-day, why, there’s nobody will find

fault.”

Accordingly the squirrel was bought, and carried home without any of the

other children having seen it, and with Harry’s assistance it was safely

hidden away till Herbert’s birth-day; and Caroline ceased to mourn for the

bird, though she was often sorry for its sad end.

Herbert’s birth-day happened during the time their cousins were with them,

and, as was the custom, they had a picnic to a ruined castle a few miles

distant. The day was beautiful all throughout, and a happier company of

children could not have been found than those that set out that morning

along with Mr. and Mrs. Ashcroft in the waggonette. The table-cloth was

laid on the bright green turf before the castle, under the shade of a

large sycamore, and when the ruins had been inspected they all sat down

and enjoyed a hearty meal. Then, while the girls gathered wild-flowers,

the boys went off with Mr. Ashcroft on what Charles called “an exploring

expedition;” and on their return they climbed up the wild cherry-trees

that grew in abundance in the neighbourhood, and shook down the ripe fruit

upon the girls’ heads, who managed to fill their baskets amidst much fun.

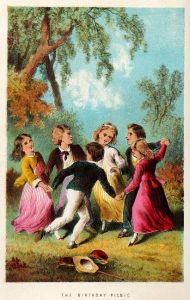

After this, and while Mrs. Ashcroft rested, the children joined hands and

After this, and while Mrs. Ashcroft rested, the children joined hands and

danced round in a ring, as may be seen by turning over to the first

picture in this book, which is called “the frontispiece.” There had been

much laughter before the ring could be formed so that each girl should be

separated from her brother, and stand between two cousins; but once this

was arranged, off they danced, round and round, till their feet could not

dance any longer. They then flung themselves down where Mrs. Ashcroft was

sitting, and had a quiet but happy hour’s rest before going home. The day

had passed so pleasantly as to be long remembered by them all; and Herbert

experienced during these holidays, for the first time in his life, that

the truest pleasure consists, not in gratifying one’s own wishes, but in

trying to make others happy.